Jeffrey Miron

Do government policies result from good intentions or from the self-interest of those who expect to benefit?

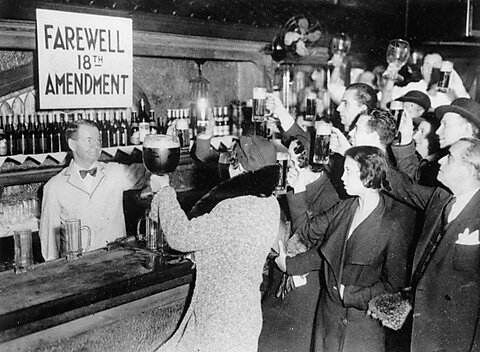

Often, the answer is “both.” The classic illustration is US alcohol prohibition. Baptists thought it saved souls; Bootleggers believed it generated excess profits for those willing to break the law.

New research applies this perspective to

the rise and fall of gender-specific, so-called protective labor laws between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries. These laws imposed work restrictions on women that did not apply to men, and they were presented as measures to protect women’s health and well-being.

And yet, these laws

often curtailed women’s access to employment, thereby increasing the income of households that depended primarily on male earnings. … [S]tates were more likely to pass restrictive labor laws when a larger share of their voting population consisted of households that would economically benefit from limiting women’s employment.

Intervening in markets empowers both good and bad intentions.